The Ocklawaha River

Credit: State Archives of Florida

Sponsored by Florida Defenders of the Environment.

In north central Florida, around 8,000 acres of floodplain soils are burning.

The imperiled floodplain spreads out below the Kirkpatrick Dam, an earthen dam that has impounded the Ocklawaha River since its construction in 1968 as part of the ill-fated Cross Florida Barge Canal. The approximately 7,200-foot-long dam prevents the floodplain from receiving its historic, natural fluctuations in water. As a result, there is an excessive amount of oxygen in the soil and not enough moisture, causing the soil to chemically react—or burn—at a very slow rate.

“We call this oxidation,” Robin Lewis, professional wetlands scientist and vice president of Putnam County Environmental Council, said. “If the soils are exposed to air for too long, they combine with oxygen and basically burn very slowly.”

For the wetlands below the Kirkpatrick Dam, so long as the water remains upstream and out of reach, there is no way to stop the burn.

Floodplain soils, composed of decaying roots, leaves, twigs and other minerals and organic matter, accumulate over hundreds of years, providing a nutrient-rich stew that can support up to 1,000 times as many species as an adjacent river.

“You've got all these species, birds in particular, that use floodplain wetlands,” said Lewis. “They use the trees."

"There are forty or fifty species of birds that are absolutely dependent on tall, healthy trees and the food supply found there for nesting and raising their young.”

Without a normal flood cycle of 60 to 90 days per year, though, there is no surge of nutrients inviting microscopic organisms. There is no shallow, murky refuge for juvenile fish to grow and to escape larger, aquatic predators.

“If you're a very tiny fish, just an inch long, the species that want to eat you are going to be swimming in deeper water,” said Lewis. “You need to go some place that's shallow. You need to find a place for protection and food supply. Then, as you mature, you can go out into the deeper water.”

In a parched floodplain, the soils begin to dry. The organic blend of leaves, twigs and other detritus collapses and the entire area sinks. This process is known as subsidence and is a direct result of moisture loss.

Subsidence causes trees to become unstable. Specialized roots that have adapted to flooding are exposed as the ground breaks down. The naked roots are then unable to support top-heavy trees.

Eventually, those same trees begin to topple. More habitat for nesting birds is lost. The forest canopy becomes pockmarked with holes previously filled by spreading maple, cypress, tupelo and oak. Without a stable environment and regular food source, the ecosystem—once vocal with the varied noises of bird rookeries and croaking frogs—goes quiet.

“We've seen massive evidence of this taking place,” said Lewis, of the dry Ocklawaha floodplains. “If the soils are inundated on a regular basis, they don't oxidize. That's the secret. You have to have enough water over the soils to prevent oxidation, to prevent oxygen from getting to the soils.”

When the Ocklawaha River was impounded in 1968, the river's natural flow was held back, creating the Rodman Pool—a pool of water more than 15 miles long and covering 15,000 acres.

The pool was intended to hold barge traffic traveling the length of the Cross Florida Barge Canal.

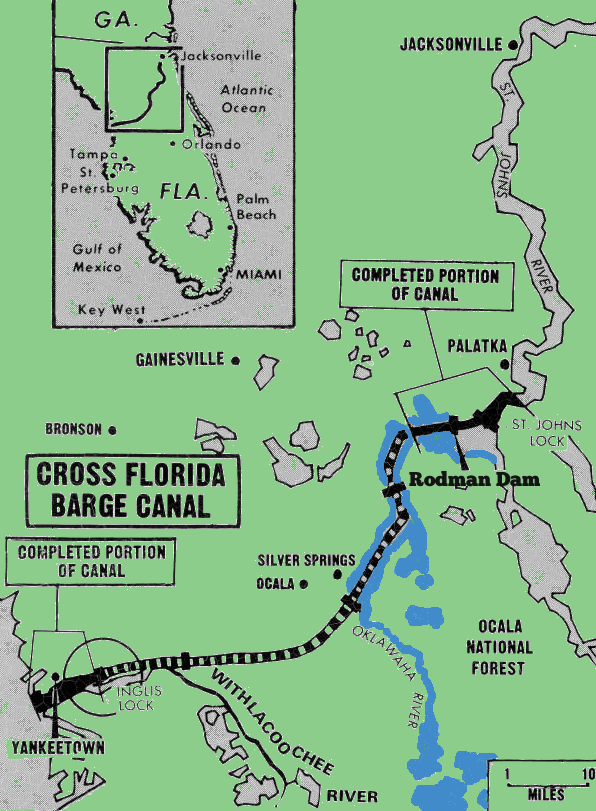

Had it been completed, the canal would have provided an interior water route for barge traffic traveling between the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean, shaving hundreds of miles off commercial transportation and providing a sheltered, presumably safer route.

In 1971, however, just three years after the Kirkpatrick Dam was completed and the Rodman Pool was created, President Nixon signed an executive order halting further construction of the barge canal, citing the irrecoverable damage that could occur to the “uniquely beautiful, semi-tropical stream.”

Slightly less than one-third of the canal had been completed, at a cost of approximately $74 million, when construction was stopped.

Environmentalists feel that the cost of the barge canal exceeds the initial construction cost, stating that the remnants of the now-defunct canal project endanger waterways and unnecessarily cost taxpayers upwards of $1 million a year.

Principally, environmentalists cite the Kirkpatrick Dam's continued impact on the Ocklawaha River. It is an impact, they say, that affects waterways and water quality as far away as Jacksonville, Fla., a city located more than 100 miles downstream from the dam.

For the Ocklawaha, what had been more than 80 miles of free-flowing river bordered by a neighborly corridor of floodplains became a segmented, disconnected and supposedly purposeless system that demands regular maintenance and prohibits the historic migration patterns of endangered species.

What had been once described by Sidney Lanier as “if God had turned into water and trees the recollection of some meditative ramble through the lonely seclusion of His own soul” became a concrete-spillway seesaw with too much water on one side and not enough water on the other.

“The Ocklawaha River has to be restored,” said Lewis. “The Kirkpatrick Dam has to be breached. We've got to restore a free-flowing river.”

Paul "Ocklawahaman" Nosca walks through standing water in a healthy floodplain along the riverine section of the middle Ocklawaha River. Photo by Matt Keene.

Since receiving statehood, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission estimates that total wetland area in Florida has decreased by approximately 44 percent.

Because of their flat and nutrient-rich soils, many healthy floodplains were drained, logged and turned into farmland. Across the United States, this has contributed to a more than 70 percent loss of floodplain forested swamps, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. A long-held perception that swamps are a no-mans-land, devoid of any intrinsic value, has further spurred this loss.

The diverse functions of a thriving floodplain, though, are as subtle and delicate as their slow-moving waters and sediment-filled soils. The saturated soils are high in productivity and food value. In dry years, a floodplain may be the only source of shallow water for wetlands-dependent species like wood ducks, river otters and cottonmouth snakes. Up to 45 percent of the species inhabiting wetlands, according to the EPA, are rare and endangered.

The loose, alluvial floodplain soils serve another purpose: the soils scrub and clean water, removing overloaded nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorous and helping to curb the emission of greenhouse gases such as nitrous oxide. Some wetlands are capable of removing up to 90 percent of nitrogen and phosphorous from runoff water.

“They clean the water,” said Lewis. “We know that there are chemical processes that remove nitrates and convert them to a gas. Its called denitrification and its a common process in floodplain wetlands.”

Microorganisms, plants and algae all absorb, use and convert these nutrients, removing them from environmental systems. In Florida, where out-dated septic systems, excessive fertilizer use and zealous groundwater withdrawals have increased the amount of nitrate and phosphorous to detrimental levels, a healthy wetland can save thousands of dollars in maintenance and treatment.

All over Florida, wetlands are being implemented for the purpose of cleaning water and removing nutrients. Orlando, Lakeland, Titusville, West Palm Beach, and Gainesville have all constructed wetlands that effectively minimize human impact while recharging the Floridan Aquifer, decrease nutrient input into groundwater and springs and create healthy habitat. According to a report by the Florida Springs Institute, total nitrogen in the Orlando Easterly Constructed Wetland was reduced more than 65 percent over a period of 14 years.

These systems protect groundwater and nearby surface waters such as springs, rivers and estuaries as well as provide wildlife habitat and aesthetically-pleasing passive public areas.

Around 50 miles from Rodman Dam, the Paynes Prairie Sheetflow Restoration Project aims to create 125 acres of new wetlands and restore an additional 1,300 acres of natural wetlands within Paynes Prairie Preserve State Park. The project is a joint effort of the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, the Florida Department of Transportation, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, the St Johns River Water Management District, Alachua County and Gainesville Utilities. It represents a $26 million investment that fixes more than 70 years of disruption to the natural ecosystem while preserving regional water resources.

“The Department has developed an approach to environmental protection focused on solid research and aggressive restoration,” said DEP Secretary Herschel T. Vinyard, Jr. “We realize that understanding the problems of the past is the first step in moving forward to solve them. We are thrilled that innovative local solutions like this bring environmental restoration to the doorstep of everyone in Alachua County.”

The chemical processes at work in a natural wetlands area are an essential part to removing nutrients. In Rodman Pool, where rampant growth of floating and submerged aquatic plants require the pool to be drawn-down every three to four years—a treatment that involves opening the floodgates of the dam and releasing the backed-up water—any nitrogen absorbed through the plant tissue never actually removes excess nitrates. As the plants die, either naturally or due to the draw-downs, they decompose and end up as mud deposits. Then, over time, the nitrates enter back into the water column.

Along the riverine (upstream from Rodman Pool) section of the Ocklawaha, however, nitrates are truly removed from the system due to the river's access to natural wetlands, according to a technical report written for Save Our Big Scrub, Inc. and the Putnam County Environmental Council. More than 50 percent of the documented decrease in nitrate levels along the river take place in this section, before having any contact with the Rodman Pool.

The construction of the Kirkpatrick Dam and devastation of the wetlands above and below stream saw the loss of a free, natural, nutrient-cleansing machine, approximately 15,000 acres in size. As a result, the burden and cost of nutrient-removal has been felt by Florida taxpayers for more than forty years.

“We already have, below the dam, about 8,000 acres of stressed wetlands that do not get enough water,” said Lewis. “And then, above the dam, we have 7,000 acres that have too much water. All that habitat, all that water-cleansing power, could be harnessed to improve the environment and improve the river. But it's got to be restored.”

Next: Environmentalists file legal challenge, call cattle ranch a 'recipe for disaster.'