The Ocklawaha River

Credit: State Archives of Florida

Sponsored by Florida Defenders of the Environment.

If approved, 6,371 grass-fed cattle will spend 158 days fattening up on the North Tract of the ranch formerly known as Adena Springs, aka Sleepy Creek Lands in Fort McCoy, Fla., before slaughter.

In that time, the cattle will produce a total of 68 million pounds of manure—the weight of more than 24,000 2014 Toyota Corollas—on the 7,200-acre property.

This has environmentalists worried, as they fear nutrients will seep into both groundwater and nearby Mill Creek, a braided tributary to the Ocklawaha River.

“With the cattle and slaughterhouse right by Mill Creek, all the manure, pesticide and fertilizers could run into the creek and then into the Ocklawaha River,” said Karen Chadwick, an eco-tour guide and local resident. “It could be very detrimental to the health of this entire system.”

Concerned over the potential impact, Sierra Club, St Johns Riverkeeper and citizens Karen Ahlers and Jeri Baldwin have all petitioned for an administrative hearing challenging the approval and recommended approval by the St Johns River Water Management District of an Environmental Resource Permit and, respectively, a Consumptive Use Permit for water use.

“Due to the high amount of nutrient pollution that will be coming off of this site, both in the groundwater and the surface water, an environmental resource permit was necessary,” said Riverkeeper Lisa Rinaman of St Johns Riverkeeper. “But we don't feel like the applicant is giving enough reasonable assurances that there won't be significant nutrient pollution in an area that's already severely impaired.”

The petitioners state that SJRWMD staff have failed to account for the impacts to the flow of Silver and Salt springs, the Silver and Ocklawaha rivers and “the increased nutrient loading that will result” from the cattle's manure and use of large quantities of fertilizer and water. They state that SJRWMD has not provided reasonable assurances that water resources would not be significantly affected. The petitioners also question the validity and accuracy of the scientific models used to determine a permit's acceptability.

In order to call their beef grass-fed, Sleepy Creek Lands aka Adena Springs Ranch will need 2.32 million gallons of water per day to irrigate the grass the cattle eat and to provide 12 gallons of drinking water for the livestock, per animal, per day, according to the Consumptive Use Permit application they filed in February of 2014.

More than two years ago, Adena Springs Ranch was seeking a total of 13.267 mgd, nearly six times their current water request. That request catalyzed environmental and water activists, who voiced their opposition to SJRWMD. Since Adena Springs Ranch's original permit application, less than 150 letters of support have been received by the district, while almost 6,000 letters of concern or objection have been sent, or more than six a day, on average.

“The effort we've put into it, simply because we've seen that permit go from 13.267 mgd to 2.3 mgd, that is a victory,” said Ahlers. “Whether or not we stop the project, we've made it better.”

The intense focus on reducing water use, however, allowed the approval of the Environmental Resource Permit to largely go unnoticed. The ERP will allow the ranch to modify water drainage on the site that currently drains into Mill Creek. With more than 2,000 acres of wetlands on the property, some that serve as headwaters to Mill Creek—a tributary to the Ocklawaha River, environmentalists feel that the ERP was approved hastily while using bad science.

Dark water in Mill Creek, rapidly running downstream to the Ocklawaha River. Photo by Matt Keene.

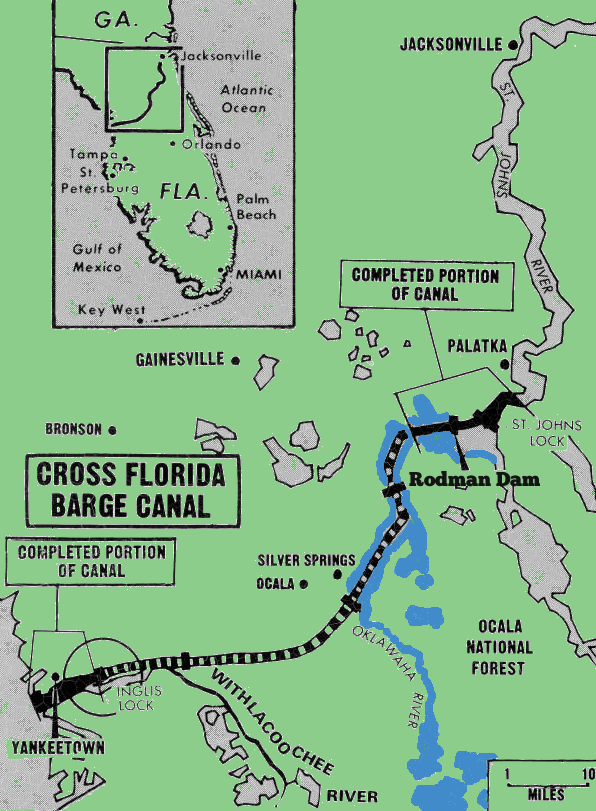

Mill Creek flows approximately five miles from the ranch to its confluence with the Ocklawaha River.

It is a braided tributary, meaning that several small streams weave through adjacent wetlands on their way to the Ocklawaha. The waters of Mill Creek join the Ocklawaha River in the riverine section of Rodman Pool, less than 15 miles upstream of the Kirkpatrick Dam.

Along this section of the pool, the backed-up waters from the dam have caused an over-abundance of aquatic plant growth that necessitates a draw-down of Rodman Pool every three to four years in order to remove the excessive growth.

“The Kirkpatrick Dam is holding water unnaturally in that area,” said Rinaman. “It is killing vegetation and trees and increasing nutrients. It's like a big petri dish. In my opinion, it's actually making the nutrient pollution problem in the area much, much worse.”

As methods of addressing nutrient pollution and waste runoff, the ranch's nutrient management plan lists cattle rotation, retention ponds and stormwater wetland buffer berms. Through the use of non-irrigated pastures and irrigated rotationally grazed paddocks, the ranch hopes to evenly spread the more than 400,000 pounds of manure added to the ground every day.

In times of high growth, the cattle will be moved each day, rotating through a series of ten paddocks around a central irrigation pivot. Additional nitrogen fertilizer will be applied to the previous paddock to help the grasses recover, as soon as the cattle have vacated. In times of low growth, the cattle will spend three days in a paddock prior to rotation. The ranch intends to apply a manure-based fertilizer, drawn from their retention ponds, at agronomic rates in an effort to minimize environmental impact. According to the Enviromental Protection Agency, though, “even when farmers apply fertilizer at the recommended agronomic rates, only 30 percent to 50 percent of the nitrogen added to the soil is taken up by the plant depending on the species and cultivar, with the rest lost to surface runoff, leaching of nitrates, ammonia volatilization or bacteria competition.”

This runoff is where potential groundwater infiltration could occur, as the ranch is within the Ocklawaha River watershed. At 2,769 square miles, the watershed is the largest tributary watershed to the St Johns River and contains both a connected chain of lakes and wetlands and a well-developed groundwater or sub-surface flow system, according to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. Groundwater flowing through the watershed discharges primarily at Rainbow Springs and Silver Springs, the Ocklawaha River's major tributary.

FDEP has called for a 79 percent reduction in nitrates at Silver Springs, noting that sources of nitrates include “inorganic fertilizers applied to agricultural fields, yards and golf courses along with organic sources, including domestic wastewater and residuals, septic tank effluent and animal waste from equine and cow/calf operations” and that the contaminants enter the groundwater “often by way of stormwater runoff.”

“I'm no expert but I know that water runs downhill,” said Ahlers. “The Ocklawaha is downhill from Adena's operation. Rain that falls on the ranch and irrigation water will be polluted by cattle waste and fertilizer. Some will soak into the ground and have a negative effect on groundwater. The rest will be transported via Mill Creek to the Ocklawaha.”

Cypress knees rise up under the single-lane Mill Creek Bridge. Photo by Matt Keene.

According to the EPA, chicken, hog and cattle excrement has polluted 35,000 miles of rivers in 22 states and contaminated groundwater in 17 states.

“We believe that this is simply the wrong use for this property,” said Rinaman. “We're not opposed to grass-fed beef, but in this area, in this sandy soil, in this impaired state of the waterway, we believe this is a recipe for disaster. This should not be the use on that property.”

Had the legal challenge not been taken, the SJRWMD Governing Board would have made a decision on their CUP permit request at its June 10 meeting. Now, the decision will have to wait until the petitioners plead their case before an administrative law judge, most likely in August.

As citizens, Ahlers and Baldwin don't have the resources of larger environmental organizations to protect them in this legal challenge. They have, however, earned their support and commitment.

“Somebody has to say I've had enough,” said Ahlers. “Somebody has to draw a line. Citizens need to do that. Citizens need to stand up and be counted. Citizens need to take responsibility for seeing to it that public resources are protected.”

Next: Dam disables southernmost bass habitat, threatens endangered species