The Ocklawaha River

Credit: State Archives of Florida

Sponsored by Florida Defenders of the Environment.

Even though a female may lay as many as 3 million eggs at one time, good luck finding a native striped bass on Florida's east coast.

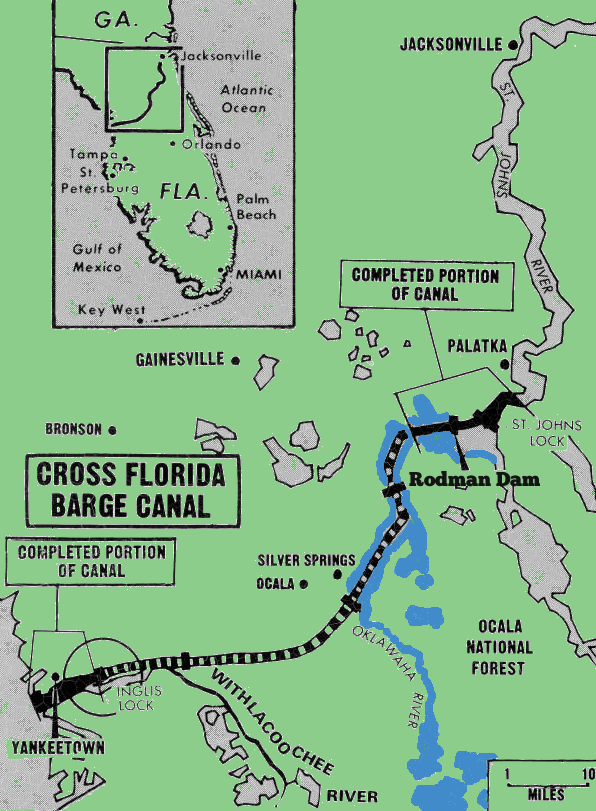

The St Johns River, listed as the southernmost river in North America suitable for the popular game fish to spawn, has been incapable of supporting a spawn run since 1968, when the Kirkpatrick Dam was built across the Ocklawaha River. The dam paralyzed upstream access to the cool, fast flowing water essential for the bass's successful reproduction.

“We're at the southern temperature range for striped bass,” said retired fisheries biologist Jim Clugston. “The basic biology of any fish is a temperature range in which they can live, another in which they feed and grow best, and another smaller temperature range required to spawn.”

In Florida, more than 1.4 million anglers fish approximately 3 million acres of lakes, ponds and reservoirs and 12,000 miles of fishable rivers. This has an economic impact of $2.4 billion and supports around 23,500 jobs. Former Florida Governor John Martin, in 1925, said that game and fish were “one of the state's most valuable commercial assets, as well as one of her greatest tourist attractions” and that “our fresh and salt water fish should be conserved.”

That has been the mission of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, which protects and manages more than 200 native species of freshwater fish and more than 500 native species of saltwater fish. For the striper—a fish that has attracted anglers for generations and is the state fish of Maryland, Rhode Island and South Carolina, and the state saltwater fish of New York, New Jersey, Virginia and New Hampshire—the FWC has taken a position of replacement as opposed to restoration, annually stocking hatchery-reared striped bass fingerlings.

This places the burden of maintaining a once-native fish on Florida taxpayers, as a free-flowing Ocklawaha River would allow suitable refuge for the stripers and provide, as an article in Florida Sportsman stated in August, 2012, a “sensational … local economic benefit of having the only native spawning striper fishery in Florida.”

Paul "Ocklawahaman" Nosca paddles up a small tributary of the Ocklawaha River. Photo by Matt Keene.

As sea levels rose following the last Ice Age and stream gradients and river flows began to resemble their modern courses, striped bass habitat was whittled down to a single river system along Florida's Atlantic Ocean: the St Johns, where the spring-fed Ocklawaha River provided the necessary and specific qualities—a quick flow, cool temperature and 48-plus-mile length—essential for the popular game fish to spawn.

Stripers are common in coastal and river systems further north along the Atlantic Coast where cooler waters and faster flowing rivers provide more suitable habitat. Florida's warm temperatures, however, limit livable range. While more northern striped bass migrate into coastal waters upon maturity, most southern populations reside year-round in rivers or estuaries.

The Ocklawaha River, fed by more than two dozen springs, including the first-magnitude Silver Springs, and accessible via the St Johns River, remained at a cool enough temperature for the riverine freshwater fish to survive when summer water temperatures rose in nearby coastal waters.

Prior to 1968, various Florida newspapers would report the presence of striped bass up the Ocklawaha River. The Palm Beach Post-Times reported in 1962 that “eighty-four striped bass were brought into one fishing camp alone on the St Johns during the past year, and some of the stripers at Silver Springs are now up to the 25-30-pound bracket.”

Believed to live up to 30 years, 2- to 4-year-old striped bass migrate into swift-flowing, freshwater rivers to spawn. Seven to eight males will typically surround a female around dusk, bumping her toward swift currents at the river's surface. The female will broadcast up to 3 million eggs into the current. Discharged eggs are then fertilized by the released sperm of males. At this point, the semi-buoyant fertilized eggs must float in river currents for approximately 48 hours. If the eggs fall to the river bottom, they will suffocate. The historically free-flowing Ocklawaha River's 56-mile length and approximate one-mile-per-hour current provided the necessary 48-hour flow that would have allowed striper eggs to hatch.

The Kirkpatrick Dam, however, severed the river, eliminating any possibility of natural spawning while mimicking a common pattern in rivers along the Atlantic coastline where construction of dams and declines in water quality decimated migratory fish populations, including striped bass. In the northeast, for instance, an average of seven dams interrupts every 100 miles of river.

“The dam has stopped the migration of many fishes from the St Johns up the river. It's very obvious with the striped bass,” said Clugston. “There are ample pictures showing striped bass in the Silver Springs area before the dam was constructed.”

Jerry Eller fishes for bass on the middle Ocklawaha River. Photo by Matt Keene.

Recognizing the impact dams have had on migratory fish populations, restoration groups, anglers, environmentalists and state and federal agencies have come together to return rivers to a free-flowing state.

In North Carolina, the removal of the Lassiter Mill Dam restored 15 miles of river and 174 miles of stream habitat that had been blocked for more than 200 years. This action has helped to revive American shad, striped bass, Atlantic salmon and sea-run trout populations. Similarly, the 1999 restoration of the Kennebec River in Maine opened up vital habitat and drew striped bass upriver to spawn. New Hampshire's Merrimack Village Dam removal cost less than $600,000 and allowed migratory fish to return to spawning grounds that had been blocked for more than 270 years, as well as connected habitat, restored natural sediment transport, eliminated operation and maintenance costs and removed a potential safety hazard.

The removal of the Kirkpatrick Dam would allow species such as striped bass, channel catfish, shad, mullet, American eel, Atlantic sturgeon and the endangered manatee to return to the upper Ocklawaha's numerous springs and tributaries, where spawning, breeding and calving would be possible. The awareness of this brought legal action against the U.S. Forest Service in 2012, when Earthjustice, representing Florida Defenders of the Environment and Florida Wildlife Federation, filed a 60-day Notice of Intent to Sue on the basis that the dam blocked the migratory route of imperiled manatees and shortnose sturgeon. The U.S. Department of Agriculture, the parent agency of the USFS, responded less than two months later, stating that “the agency would re-initiate consultation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service under the Endangered Species Act to determine the dam's impact on endangered manatee and the threatened shortnose sturgeon.”

The FWC and USFS have repeatedly expressed support for restoration of the Ocklawaha River, along with every Florida governor since Governor Reubin Askew in the late 1970s. A biological assessment of the dam's impact on endangered species, required under the Endangered Species Act, was issued on the basis of river restoration in 2001. This assessment concluded that restoration would not jeopardize the continued existence of endangered species along the Ocklawaha River Basin. Stating that they were unable to afford restoration, Florida never removed the dam and continues to operate it without a federally-required permit.

Since the biological assessments concluded that removal of the dam would not have an adverse impact, the legal action challenged that, as long as the dam is in place, there is an adverse impact on the endangered manatee and shortnose sturgeon, as well as other species dependent on a free-flowing system, such as the striped bass.

The USFS review concluded that the breaching of Kirkpatrick Dam would have no adverse effect on manatee, shortnose sturgeon or Atlantic sturgeon. USFWS also backed up this conclusion, stating their support for “partial restoration efforts of the St John's River in the area of the Rodman Reservoir.”

Next: The Kirkpatrick Dam's lasting uncertainty

Previous: Environmentalists file legal challenge, call cattle ranch a 'recipe for disaster'