The Ocklawaha River

Credit: State Archives of Florida

Sponsored by Florida Defenders of the Environment.

When environmental activist Marjorie Harris Carr was buried in October, 1997, a 'Free the Ocklawaha' bumper sticker was stuck to her casket.

Six years later, in 2003, former Florida Senator George Kirkpatrick was buried—only, as counterpoint to Carr, a 'Save Rodman Reservoir' bumper sticker was affixed to his casket.

That these two adversaries would take the battle over the Ocklawaha River and Kirkpatrick Dam to their graves was no surprise. Their herculean efforts in support of their cause brought them national recognition and lasting remembrance. A dam, symbolic of man's persistence and obstinacy, was named after the former senator. A greenway corridor, symbolic of the metamorphosis from industrial foolhardiness to wilderness contemplation, was named after the activist, a woman once mistakenly dismissed as a 'mere Micanopy housewife.'

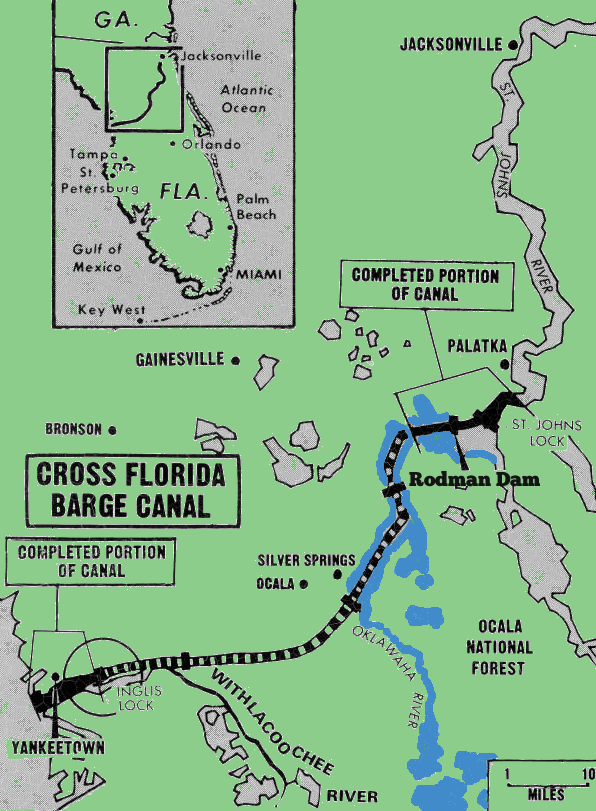

The fate of the Ocklawaha River demanded their attention, a river that in the 1960s was drifting toward the turbulent and changing sea of national identity. On one side, voices championed construction of a barge canal across the Ocklawaha as a passageway for national defense and a pathway that would secure job growth and economic development. On the other, a nationwide shift in environmental perspective was taking place, with the Ocklawaha River seen as more than a resource to be manipulated.

The river became recognized as what President Richard Nixon would call a “natural treasure” when he halted construction on the Cross Florida Barge Canal on January 19, 1971, saving the Ocklawaha River and Silver Springs from further harm but leaving it unnaturally sliced in two, to the point that some Kirkpatrick Dam supporters refer to the Ocklawaha River not as a tributary to the mighty St Johns River, but as a tributary to Rodman Pool.

In 1971, Brown Gregg, a Leesburg, Fla., engineer, specially designed a machine known as “Big Charlie” by its operators, the “Crusher Crawler” by engineers and “The Tree Killer” by environmental critics.

It stood 22 feet high, weighed 306 tons, could float at a depth of almost eight feet and could mash down as many as eight cypress trees simultaneously. The machine was used to demolish the forested land soon filled by the rising waters of Rodman Pool. The machine was not, however, used to log the land. Less than 15 percent of the region's felled trees were salvaged for lumber. In the rush to complete the Cross Florida Barge Canal and Kirkpatrick Dam, the rest were laid flat and driven into the ground or drenched with diesel fuel and lit afire.

“I think it has now come to be recognized that my tree crusher was not so bad a thing,” Gregg said of his machine. “That going through a swamp and pushing trees over and embedding them in the mud and sand is the natural way, the way nature puts those trees down. It's just evolution in a sense.”

Images of the crusher-crawler helped to galvanize resistance to the Cross Florida Barge Canal. Gregg's quote, however, pointed to the unabashedly proud sentiment of American determination that filled the country at a time when men were flying in space and the possibilities of the future seemed limited only by imagination and never by resource.

From 1950 to 1979, more than two-thirds of all dams currently existing in Florida were built.

It was an effort to tame the American wilderness and turn “useless” environmental systems into mechanisms of production. Or, as the Army Corps of Engineers put it in a 1970 pronouncement: “The barge canal will save the Ocklawaha from nature.”

On a rainy February 27, 1964, President Johnson initiated construction of the Cross Florida Barge Canal, setting off 150 pounds of dynamite to ring in the groundbreaking.

“The challenge of modern society is to make the resources of nature useful," said President Johnson at the groundbreaking, reiterating the opinion that natural systems only became useful when altered by the hand of man.

Between 1960 and 1969, an average of one dam was completed every two weeks. Of the 895 dams currently in the state, the purpose of 135 is “unknown,” according to the Army Corps of Engineers.

Rodman Pool supporters argue that the purpose of the Kirkpatrick Dam is not unknown. The dam, in their view, ensures the health of Rodman Pool and the plant and animal communities that, over the past 45 years, have tried to find a niche in the man-made system—despite multiple fish kills that have left more than 11 million fish dead and a never-ending, repetitive necessity to drain, or “manage,” the pool. Those in favor of restoration, however, believe that the Kirkpatrick Dam serves no useful purpose and instead harms the ecological well-being of not only the Ocklawaha River, but also Silver Springs and the St Johns River all the way to its confluence with the Atlantic Ocean.

These impressions upon nature speak to the heart of the contentious debate. Life, in its tenacity, will pour into the cracks vacated by production, much as plants will fill the cracks in a sidewalk or birds' nests are found in the abandoned buildings of Chernobyl. The longer a system is left in place, the more life will come—and the more people will get used to, will begin to love, the mirage they see in front of them.

Next: Florida water management district eyes river, pool of disappearing water

Previous: Dam disables southernmost bass habitat, threatens endangered species.