The Ocklawaha River

Credit: State Archives of Florida

Sponsored by Florida Defenders of the Environment.

Already losing more than 9 billion gallons of water per year to evaporation, a pool of water in north central Florida might be targeted as a source of withdrawal for water-hungry Floridians.

The St Johns River Water Management District is preparing its 20-year Water Supply Plan to address need in 18 counties through 2035. With groundwater—the preferred source—reaching its limit, the district is looking to alternative supplies, such as rivers, lakes, canals, reservoirs, storm water and seawater.

“It's getting harder to find more fresh groundwater,” said Jim Gross, technical program manager at SJRMWD. “We have to start looking at alternative sources.”

The St Johns and Ocklawaha rivers are potential sources capable of providing more than 200 million gallons of water per day combined, according to SJRWMD's draft Plan.

This has environmentalists worried, stating that the St Johns and Ocklawaha rivers are already stressed systems and that withdrawals would worsen existing pollution problems, reduce flow and adversely impact wildlife, fisheries and submerged vegetation. They also cite an estimated cost of $3.9 billion and state that the SJRWMD study used to justify withdrawals is based on flawed science.

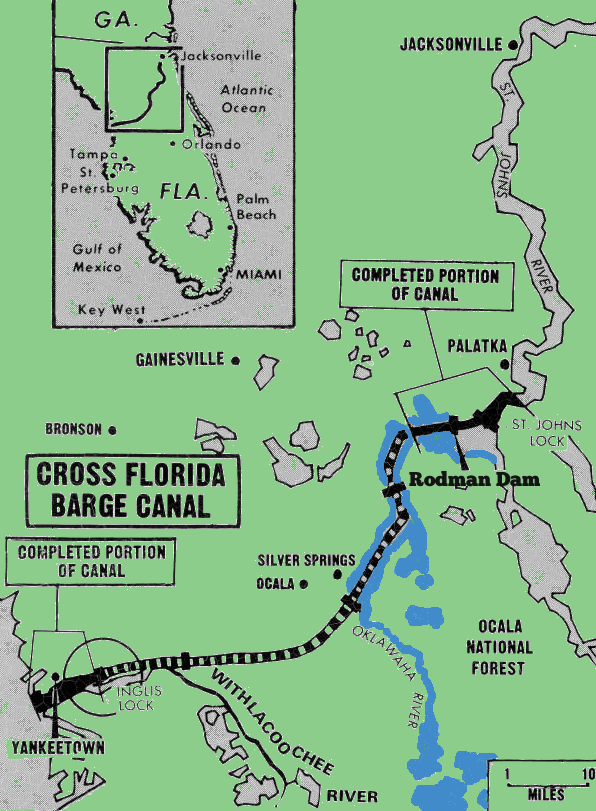

For the Ocklawaha River in particular, environmentalists fear that water withdrawals will provide a foothold permanently establishing Rodman Pool, the 16-mile-long pool created when the Kirkpatrick Dam was built across the Ocklawaha, as an Alternative Water Supply. The Kirkpatrick Dam, which currently has no clearly defined purpose and is trespassing on federal land, would then become essential, in order to ensure the availability of water in the pool. This could remove any possibility of restoring a free-flowing Ocklawaha River.

“The [Kirkpatrick] Dam would probably affect water use from the river beneficially from the standpoint of being a pool to withdraw from,” said Gross, adding that the dam is not a necessary feature for water withdrawals but that, while it could serve only as short-term storage due to its shallowness, the pool creates a more reliable source. Removal of the dam, Gross said, means that only a smaller withdrawal would probably be feasible.

“It's not a reservoir,” said Robin Lewis, vice president of Putnam County Environmental Council. “It was constructed to float barges. It was never constructed to save water. In fact, 25 million gallons a day evaporates from this system. It is wasted just by evaporation because its so shallow.”

The predominately shallow waters in Rodman Pool heat quickly under the Florida sun, speeding up evaporation. Exotic plants exhale water vapors through the leaves, stems and flowers, a process known as transpiration. Wind further increases the rate of transpiration. This combined evapotranspiration in the pool leads to a significant loss of water in the basin, calculated at around 25 mgd.

“There is no water left in that system that could be removed,” said Lewis. “It doesn't make any difference whether its 10 million gallons a day or 100 million gallons a day; It's not there.”

The Ocklawaha River, according to Lewis, has seen a 36 percent reduction in flows over the period of record, due to groundwater withdrawals and the blockage of water at Moss Bluff Lock, upstream from the Silver River.

As its largest tributary, most of the Ocklawaha's flow comes from the Silver River. Silver Springs, the artesian well that historically discharged more than 500 mgd into the Silver River, has seen a precipitous decline in flow due to consumptive water use. This decline in flow directly affects the amount of water reaching the Ocklawaha.

According to Dr. Robert Knight of the Florida Springs Institute, water management districts define significant harm to springs at around a 10 percent reduction in flow. Silver Springs is currently at a 24 percent reduction from its historical flow.

“Lowered spring flows on the Ocklawaha River would certainly represent a potential problem for using the river as a water supply source,” said Gross. “if we continue to pump groundwater as our main source of water into the future, we would expect that springs would decrease. We're going to need to somehow stabilize the withdrawals from the upper Floridan Aquifer and try to protect, and in some cases maybe restore, spring flows while we develop alternative sources.”

Kayaker Ryan Cantey paddles down a springrun soon to be flooded by the rising waters of Rodman Pool. Photo by Matt Keene.

In an effort to stop water use from the St Johns or Ocklawaha rivers, Putnam County Environmental Council, supported by the Public Trust Environmental Legal Institute of Florida, St Johns Riverkeeper, Florida Audubon Society, and Florida Defenders of the Environment, challenged, in 2009, the designation of the rivers as Alternative Water Supplies, stating that SJRWMD has “failed to give conservation priority.”

They argue that the designation of the rivers as Alternative Water Supplies may devastate the environment. When adopted as part of a district's Water Supply Plan, Alternative Water Supply projects are entitled to “priority funding attention." Local governments must develop the Alternative Water Supply assigned to them in the Plan, otherwise the water management district will impede any growth. Water management districts are also allowed to pay up to 40 percent of the cost to construct facilities needed to tap non-traditional sources designated as Alternative Water Supplies, even for private, for profit companies.

More than four years since filing, the case has still not been scheduled for a hearing. The legal challenge interferes with SJRWMD's ability to adopt the Water Supply Plan.

According to state Sen. Paula Dockery, Alternative Water Supplies were not to be “conducted in a manner that would adversely impact the areas where the water was withdrawn.” The legal challengers believe that SJRWMD's Plans “represent a clear misinterpretation of the AWS Law” and “a series of horrendous policy decisions that are not consistent with the public interest.” They argue that the water quality in the rivers are degraded and continues to decline, leading to nuisance plants, loss of productivity, oxidizing floodplain soils and subsidence.

A gator stays warm on the middle Ocklawaha River. Photo by Matt Keene.

Groundwater has historically been the first choice for water supply, due to its high quality, low cost and close proximity to users.

Surface water, such as lakes or rivers, tends to be of lower quality and more difficult—costly—to treat, due to sediment, soil particles, excess nutrients and rain-dependent, variable flow. Because of “the freshwater contribution of Silver Springs,” the draft Water Supply Plan identifies the Ocklawaha River as having good water quality. Fed by Silver Springs, the river is, essentially, a groundwater outlet flowing along the edge of a national forest.

“The Ocklawaha River has very high quality and doesn't have problems with salinity like the St Johns River,” said Gross. “The flow in the river is reliable, because it is partially spring driven, especially below the confluence with the Silver River.”

The health of Silver Springs has already degraded significantly, according to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. An increase in organic fertilizer runoff has led to FDEP calling for a 79 percent reduction in nitrates at the world-class springs.

Environmentalists warn that withdrawals could worsen nutrient problems in the river and argue that SJRWMD is using the findings from a flawed study to justify surface water withdrawals. The National Research Council reviewed this study, the District's Water Supply Impact Study, and found that “the modeling conducted by the District did not have a water quality component.” The potential effects of stormwater runoff on the environment were considered to be “outside the scope of the WSIS.”

According to the NRC, the SJRWMD also failed to consider potential effects to the Ocklawaha River in its study, focusing only on “potential effects of the withdrawals on the hydrology and ecology of the St Johns River.”

“They treat the ecosystem in tiny bits and pieces,” said Lewis. “We've got to overcome that and understand that the system is interconnected.”

Instead of the District limiting the approval of consumptive use permits or stressing conservation, some feel that the proposed river withdrawals are being viewed as primary options.

Environmental groups such as St Johns Riverkeeper argue that “despite the looming water shortages, our state water management districts continue to issue frivolous consumptive use permits that will further deplete our aquifer.” In February, 2014, for instance, SJRWMD approved a permit for California-based Niagara Bottling, allowing the plant to about double its pumping of the Floridan Aquifer to nearly one million gallons a day.

“Conservation seems to be no one's priority,” said Karen Ahlers, executive director of Florida Defenders of the Environment. “The Ocklawaha as an alternative water source is the next cheapest thing when you're talking about large quantities of water. Its far cheaper than desalination, but it bears a high ecological cost on the river ecosystem.”

The draft Water Supply Plan projects that water conservation can reduce 2035 water demand “by 84 to 214 mgd, depending on the level of implementation.”

“A lot of people have a hard time being asked to reduce their water intake while the legislators are issuing these huge permits,” said Lars Andersen, local eco-tour guide and owner of Adventure Outpost in High Springs. “There's a real disconnect there.”

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, as much as 50 percent of water used outdoors is wasted due to evaporation, wind or runoff caused by inefficient irrigation methods and systems. Nationwide, nearly one-third of all residential water use can be attributed to landscape irrigation.

“There probably are some more cost-effective things that can be done in the immediate future rather than developing alternative water supplies,” said Gross. “There are some conservation options that could be pushed a little harder that might be more cost-effective then going to the alternative supplies.”

Conservation, however, is “based on voluntary consumer actions, with encouragement through education, and a level of financial incentives,” according to the Central Florida Water Initiative. Many environmentalists feel that voluntary measures are not sufficient and that all opportunities to use existing water resources more efficiently need to be looked at before finding new sources of water.

Similarly, the Fourth Addendum of SJRWMD's 2005 District Water Supply Plan stated that “analysis indicates a reasonable possibility that a substantial portion of the projected increase in SJRWMD water use between 2005 and 2025 could be met through improved water use efficiency, provided aggressive programs are implemented.”

“The bottom line is that water conservation does work, can potentially meet most if not all of our water supply needs, and is much more cost-effective and environmentally-responsible,” stated St Johns Riverkeeper in January, 2014.

Next: Florida officials determine maximum allowable harm to rivers, springs