The Ocklawaha River

Credit: State Archives of Florida

Sponsored by Florida Defenders of the Environment.

As peninsular Florida was formed, so was the Ocklawaha River.

Coursing out of the central spine of the emerging peninsula, the river twisted and bent north and then east until it emptied into the St Johns, a river much younger than the ancient Ocklawaha.

During wet, rainy periods, the river swelled, filling adjacent floodplains and agitating nutrient-rich soils. In dry times, the river rushed, clarified by the groundwater pulsing out of the more than 30 springs staged along its length, including the uniquely powerful Silver Springs, an artesian well forming the Ocklawaha's largest, and most influential, tributary. This cycle of rain and drought shifted nutrients and saturated soils, allowing for the growth of rich, diverse ecosystems in the surrounding basin.

With development, though, came the need to divert the waters fueling the Ocklawaha River. The Floridan aquifer was tapped. Parts of the river were modified. Southern floodplains were cleared and the dark, primordial soils were cultivated. Water use increased, satiating agriculture, feeding families, towns, lawns and golf courses.

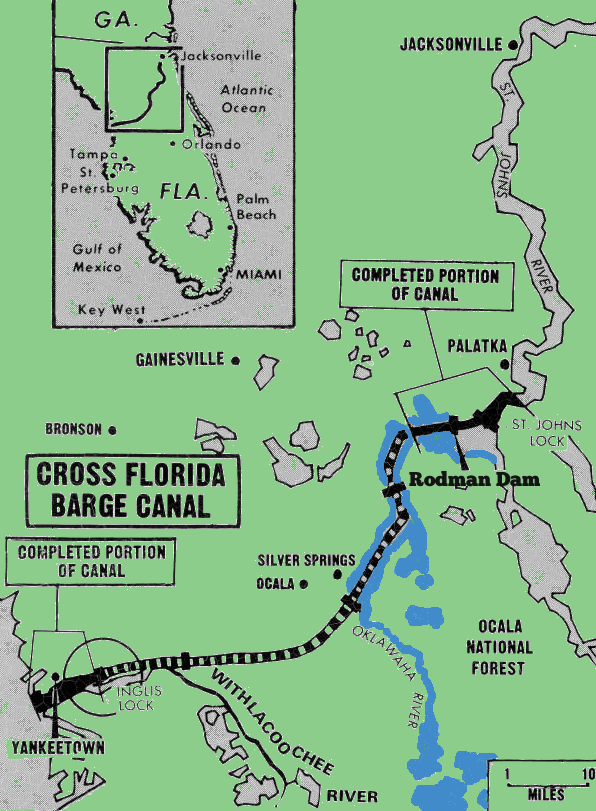

A dam was built. The natural flow of one of the peninsula's oldest rivers was appropriated by the scientific estimations of progress.

Now, science must determine the limits of wet and dry. Governing boards must decide how much water is too much and how dry is too dry. The legal parlance is Minimum Flows and Levels and they are to be established for the lower Ocklawaha River this year. MFLs will determine the extent to which users can take water that would otherwise flow down the Ocklawaha before it is too much. Before the river is significantly harmed—a murky legal designation that allows some harm, but prevents other.

“Minimum Flows and Levels are still in development, but when I talked to the scientists, it's looking like there are going to be some fairly significant constraints on the available water supply,” said Jim Gross, technical program manager of Water Use Planning and Regulation at St Johns River Water Management District, the office directed with managing water resources in northeast and east-central Florida.

According to SJRWMD's draft Water Supply Plan, a 20-year plan for ensuring available water resources that meet expected population growth, MFLs define “a range of minimum acceptable hydrologic conditions” necessary to prevent significant harm to water resources or ecology, based on water withdrawals.

Significant harm, according to water management districts, is equal to a reduction in flow by an established percentage. The percentage comes from a computer model, not from actual flow, and not from the historical or optimal conditions. Computer models calculate the percentage based on recorded water flows—typically those in the 1990s—which have often been recorded after water bodies have already been impacted by groundwater withdrawals.

Critics contend that the percentage is “seemingly arbitrary” and argue that many water bodies in Florida are already experiencing significant harm from excessive water withdrawals and that, instead of defending the health of rivers, springs and lakes, water management districts are defending water users and approving dangerous consumptive use permits.

The result, according to John R. Thomas, a lawyer involved with Florida water law and MFLs for more than 20 years, is that “MFLs once believed to provide a bright red stop sign beyond which further withdrawals would not be allowed are now just a speed bump to be navigated around.”

Take Florida's Ichetucknee and Santa Fe rivers.

Fed by springs, the rivers are directly impacted by groundwater withdrawals. The more water taken out, the less contributes to the rivers' flow.

Arguing that the state is not protecting those water bodies, environmentalists are taking legal action against the Santa Fe and Ichetucknee Minimum Flows and Levels proposed by Florida's Department of Environmental Protection.

"The proposed MFL rule for the Lower Santa Fe and Ichetucknee rivers states that both systems should be 'in recovery,' meaning that steps need to be taken to restore their flows,” stated Lucinda Faulkner Merritt, staff assistant with Ichetucknee Alliance. “Yet, the same rule refuses to recognize that current water users are part of the problem and refuses to demand that they make any changes in their water use. This makes no sense and ensures that flows in both rivers will continue to decline. The Ichetucknee Alliance believes that if we are to save our springs and rivers, we all need to make changes in the ways we use water."

Since the proposed MFLs are not officially established yet, the Suwannee River Water Management District is not currently considering them when deciding whether or not to approve a water use permit. Also, existing permit holders will not be required to comply with the protections until 2019, or three years after the completion of a new groundwater flow model, whichever comes first. Existing permit holders up for renewal will also be approved for up to 20 years of water use, so long as they do not seek an increase in water withdrawals.

For the Ocklawaha, environmentalists fear similar concessions will be given to permit holders at the expense of the river's health. SJRWMD's draft Plan already concedes that “current analyses of the draft MFLs for Silver Springs/Silver River indicate that they will be below MFLs by 2035.” If the 2035 assessment status remains below MFLs, “the District will develop strategies and adopt them at the same time as the MFLs.”

The strategies to possibly be adopted are part of 1997 legislation that required all water management districts to establish a schedule and priority for setting MFLs, and consists of “prevention” strategies and “recovery” strategies.

The strategies do not, though, stop the approval or renewal of water use permits. Critics contend that they “do very little to prevent or recover anything.”

At the same time MFLs are being developed for the Ocklawaha, SJRWMD has announced that the Ocklawaha and St Johns rivers are being considered as alternative water supplies in the 20-year Water Supply Plan.

According to the draft Plan, “alternative water supply projects and management techniques are needed to supplement available groundwater.” The draft Plan projects taking more than 200 million gallons of water per day, combined, from the St Johns and Ocklawaha rivers to meet predicted water needs.

Any withdrawals from the Ocklawaha would eventually need to be vetted by the soon-to-be established MFLs.

“The district would likely be doing some additional studies to identify environmental and regulatory constraints to withdrawals from the river,” said Gross. “Whether those would be Minimum Flows and Levels or some other type of constraint remains to be seen but the district would certainly need to know what the limits would be without creating significant harm to the river itself.”

According to Sonny Hall, technical program manager at SJRWMD, the establishment of MFLs on the lower Ocklawaha River is expected to take place late this year, with public comment and peer review more than likely taking place in October and rule making in December.

Next: Shedding water

Previous: Florida water management district eyes river, pool of disappearing water