The Ocklawaha River

Credit: State Archives of Florida

Sponsored by Florida Defenders of the Environment.

Inside a hollow multi-centennial cypress tree along the middle Ocklawaha River. Photo by Matt Keene.

I called it my lake, though it was never fully mine.

Rather, it was mine in the way that oversteps language; the way that one says “my friend” or “mon ami.”

That lake was my companion. It was where I would find myself on long summer days between school years. I had 180 acres of central Florida uplands to wander, yet my steps always condensed into that one small lilypad-speckled pool of water.

Com*pan*ion. (n). one who is frequently in the company of, associates with, or accompanies another.

It was the vortex of a sandy whirlpool with the aroma of long-leaf pine and drippings of pinecone. It pulled me inward, closer and closer, until my lazy summertime orbit tightly circled the lake's spongy outer edges.

The hours of the day mirrored my summer-drunken circles, my exploratory ellipses. I was the hand of the clock, setting the day's pace and teasing its boundaries, disbelieving that fall could ever come.

Unknowingly, my rambling circuit followed the archaic shedding of central Florida waters. Where I roamed, the water also roamed. We were both pulled to the low points, the mild depressions between millenia-old uplifted sand ridges. We both explored the wettest floodplains, seeping into black muck in search of the slightest path of moving water.

If I could have, I would have followed the water further and oozed into the soil, dripped into the spongy limestone, flowed through the aquifer, burst out of the springs, flooded into the rivers, drained into the ocean.

White wine is the usual companion of fish.

On average, our bodies are made up of around 65 percent water. Perhaps in those days my water-weight submitted to the forces of hydrology, hypnotized by some evolutionary directive to follow the movement of the clouds and the flow of the rain.

In fact, if the surface is rippled just right, our similarities appear downright genetic. My cells have been continuously renewed under the Florida sun and Florida rain. I have drunk the waters of Florida's underground aquifer, feasted on the sweetness of Zellwood corn, plucked wild low-bush blueberries and eaten more than a few bluegill and bass pulled from surficial lakes and streams. This land and its waters sustained me, taught me, sheltered me.

I am its child, born again.

There once was a hunter named Narcissus. He was proud and arrogant, confident and boastful. Nemesis, the spirit of divine retribution against hubris, attracted Narcissus to a pool of shimmering water, where he saw his own reflection and fell in love with it. Narcissus died, unable to leave the beauty of his reflection.

My lake is connected to the Atlantic Ocean by more than 130 miles of shedding water.

It is a small speck on the southern edge of a 2,679-square-mile basin known as the Ocklawaha River watershed. The watershed drains northeast through a series of connected lakes, swamps and wetlands along the state's high ridge, encouraging water into the Ocklawaha River, where it then flows to the slow, brackish lower basin of the St Johns River, and then to the salty spray of the Atlantic.

Along the Ocklawaha's serpentine path, translucent groundwater from the Floridan aquifer pours in through numerous springs, bursting into the river like fireworks on a moonless night.

Silver Springs, one of the largest artesian wells in the world, is its most notable tributary. Historically discharging more than 500 million gallons of groundwater per day, Silver Springs redefines the Ocklawaha. Upstream of the springs, the river is murky, dark, slow-moving, reflective of the lakes and swamps that drain into it. Downstream of the springs, the river is fast and clear, deep and primal.

Long before theme parks, the Ocklawaha River was a tourism destination. Steamboats in the 19th century were specially designed to navigate the river's winding bends and cart visitors upstream to Silver Springs. Ulysses S. Grant took a steamboat on the Ocklawaha. So did Harriet Beecher Stowe and Thomas Edison.

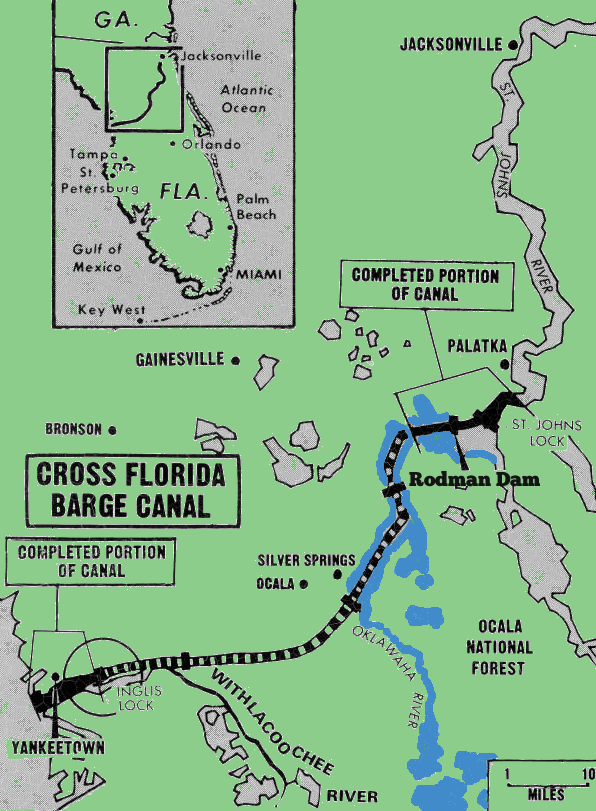

But in the 20th century, a landslide of large-scale public works came down upon the river. Federal funds and vocal supporters conjured the Cross Florida Barge Canal project into existence, bewitching the unemployed and the presidential alike with visions of a maritime lane that would funnel economic success and indiscriminately net both international and domestic wealth. Canal boosters rode an avalanche of propaganda, charging forth in a mad-dash effort to bisect the state of Florida and bring the Ocklawaha into servitude. To sever Florida's spine and harness her springs. A wild-eyed sacrifice for the god of capital.

Had it been finished, the canal would have been more than twice the length of the Panama Canal. It was to connect the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway with the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway, shortening distances and protecting ship or barge traffic from hurricanes, reefs and hostile submarines.

At the groundbreaking of the barge canal, President Lyndon Johnson said that:

“God gave us great estuaries, natural locales for harbors, but he left it to us to dredge them out for use by modern ships. He gave us shallow waters along most of our coast lines, which formed natural routes for protected coastal waterways. But he left it to us to carve out the channels to make them usable … He gave us great rivers, but let them run wild and flood, but sometimes to go dry in drought.”

Canal supporters never considered nature's value as an irreplaceable entity in their building process. For them, nature held no intrinsic value. Its value was assigned, was created, was given by man. They did not consider the river as having an inalienable and fundamental right to exist and flourish. Instead of ecosystems, supporters saw resources. Resources to be molded. Resources to be used. Resources to be sold.

To early European settlers, the ecosystems of America seemed endless and inexhaustible. How endless, though, were the old-growth forests, the herds of buffalo, or the coastal spawning runs? How inexhaustible was the Carolina parakeet or the ivory-billed woodpecker?

The eventual collapse of the Cross Florida Barge Canal project only occurred with the unwavering commitment of Marjorie Harris Carr and a coalition of individuals and organizations brought together under the emergent Florida Defenders of the Environment, who, according to Steven Noll and David Tegeder, authors of Ditch of Dreams, “would fuse sentimental attachment to the preservation of wild land with a scientific understanding of the fragile nature of ecological systems.”

Despite their success, though, the collapse of the barge canal project did not remedy the Ocklawaha's violations. It did not restore the river's right to exist. The collapse left the Ocklawaha River chained to the Cross Florida Barge Canal like a dog chained to a post long after its master has abandoned it.

To have a friend is to place their well-being equal to, or above, one's own.

To have an enemy is to disregard their wellness, to harm with intent. To act with narcissism, self-concern, hubris.

According to the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund, the “Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act and similar state laws legalize environmental harm by regulating how much pollution or destruction of nature can occur under law.” These laws, they say, codify pollution and environmental destruction. They allow harm, encourage self-interest, champion ego.

CELDF has pursued a radical legal shift, assisting local communities in crafting laws “that change the status of natural communities and ecosystems from being regarded as property under the law to being recognized as rights-bearing entities.” These local laws then recognize an ecosystem's inalienable and fundamental right to exist and flourish. These laws require governments to remedy violations and prevent harm.

“It means viewing nature as a collaborator and partner in human health and progress,” said Jane Goddard, acting director of Center for Earth Jurisprudence, an initiative of the Barry University School of Law in Orlando, Fla.

A collaborator. A partner. A companion.

“If we don't change our thinking from domination and exploitation to collaboration and true sustainability, and soon, we may do the kind of damage that cannot be undone,” said Goddard.

They called it Crusher Crawler, Big Charlie and Paul Bunyan's Bull.

According to folklore, Paul Bunyan's ox, Babe, grew so big that, whenever it had an itch, Babe would have to find a cliff to rub against “'cause whenever he tried to rub against a tree it fell over and begged for mercy.”

Contrary to the folklore, the real Paul Bunyan's Bull couldn't have heard a tree begging for mercy. Any such sound would have been smothered beneath the Bull's 270-horsepower diesel engines in the same way the Bull smothered the trees in the floodplain forests of the lower Ocklawaha River basin. This Bull stood 22-foot-high and weighed 306 tons. It was an amphibious machine operated by a two-man crew and designed to clear land in the Ocklawaha Valley where barges would, canal supporters hoped, one day float. The machine easily brought down cypress trees six feet in diameter with its concrete-filled reinforced steel push-bar. Once down, the trees stayed, crushed into the muck, where they would be “left to become part of the bottom.”

The main engineer responsible for the machine, F. Browne Gregg, said that his “tree crusher was not so bad a thing... that going through a swamp and pushing trees over and embedding them in the mud and sand is the natural way, the way nature puts those trees down. It's just evolution in a sense.”

The Bull ravaged the heavily timbered lowlands, moving at a rate of one to two acres per hour, preparing the land for the flooding that would occur when a dam was built across the Ocklawaha River.

The dam flooded more than 15 miles of riverine habitat and what remaining floodplain forests were left in the Rodman Pool area. It flooded the trees crushed by the Bull, trees that would later pop up to the surface, up from their too-soon graves like messages in a bottle, like bullet casings left at a crime scene. It flooded what would later become known as the Drowned Forest, a stump-field of trees spared an early death by the Bull, but left to drown for several decades, eventually rotting off at the water line.

When construction of the barge canal was stopped—unfinished—and the project abandoned, the dam remained. The flooded Rodman Pool remained. The living forest drowned.

The dam, the forest, the pool still remain. The dam and pool illegally occupy federal land and, if the rights of nature are to be considered, violate the Ocklawaha's right to flourish and the right for rain water draining through the Ocklawaha River watershed to one day touch the ocean. And the right for endangered manatee to swim upstream and seek refuge in the Ocklawaha's springs when winter temperatures plummet. And the right for sturgeon, channel catfish, striped bass, shad, mullet and more to feel the swift currents of the Ocklawaha. And the right for adjoining floodplain forests to experience the natural fluctuations of a healthy river. And the right for the St Johns River to find balance in the fresh groundwater of its largest tributary. And the right for bald eagles to feast on running mullet. And the right for bear to move through healthy forest. And the right for public land to regain true, sustainable value. And the right for the river to run free.

“There was a time when you were not a slave, remember that. You walked alone, full of laughter, you bathed bare-bellied. You say you have lost all recollection of it, remember . . . You say there are no words to describe this time, you say it does not exist. But remember. Make an effort to remember. Or, failing that, invent.”

One summer, my lake dried up.

The center became a muddy pit where moisture was just a shallow memory of inundation. We trudged through the muck, the lake's absence exotic, foreign, a new adventure. The muck was the lake's dry womb and we had been pulled back inside, explorers of forbidden territory.

Never did I think that the lake might not come back. Never did I think that when I brushed my teeth, I took away a part of that lake. Never did I think that lake was a part of anything but that lake.

It was a small body of water. Too small for motor boats. Just right for canoes and afternoon picnics. Just right for a dock on top of a dock, in the days when water levels were rising, not falling.

It was nestled in the shadow of the tallest point in peninsular Florida: Sugarloaf Mountain.

Companion: from Late Latin compāniō, literally: one who eats bread with another, from Latin com- with + pānis bread.

At 312 feet above sea level, Sugarloaf Mountain is a piece of the Lake Wales Ridge, formed more than one million years ago during the Pleistocene epoch. The ridge runs north to south. It is the spine of the state, a procession of humps protruding like the vertebrae of a yogi in child's pose. Over thousands of years, ground flow in the Floridan aquifer—the underground river providing most of the state with water to drink—eroded pockets and tunnels in the limestone, reducing the rock's weight and causing the ground to uplift, or rise, into a sandy series of islands in a shallow sea. As sea levels fell, the islands linked together the emerging peninsula. Water streamed off the high points, flowing down towards the receding ocean in ribbons, giving the land rivers.

Atop the emerging ridge, gnarled, reaching oaks sprawled out. Saw palmettos thicketed the floor. Pine trees sunk deep tap roots into the sand. Rain fell on the land, seeping into the soils, percolating into the aquifer, replenishing the state's limestone lungs.

My lake took shape, a measurement of the aquifer. A cool recession under the hot Florida sun. A surficial oasis, reflecting underground wellness. A part of a whole. A connection to a mighty river, above and below.

To me, though, all I could see was that lake. All I could see were the bluegill swirling around below the dock. The turtles, poking painted heads above the surface. The water-lily in full blossom. In all my childhood daydreams and far-fetched tales, the notion that the circular body of water I drifted towards on those long summer days was connected to a surging and pooling, ancient and ebbing underground river was as fantastical as anything thought up by Jules Verne.

Like the all-too rare glimpse of a Florida panther, the majesty of the Floridan aquifer lies in its mystery. It hides below our feet, yet we see it every day. It fills our pools, our rivers and our swamps. It supplies our homes and waters our farms, but we still know little about its depth or its volume. One gauges its health by the power of our springs, or the level of our lakes, or the depth of our wells.

The aquifer is recharged by rain falling onto the ground and collecting in swamps, marshes and wetlands. Water seeps down into the aquifer, passing detritus and topsoils and indigenous arrowheads and pottery sherds and filamentous roots and shell fragments and sharks teeth and fossilized rib bones and eventually leaking into the limestone karst, a spongy, porous soluble rock. The passage from surface to aquifer varies and no single data model can provide a standard, across-the-board rate. Some water in the aquifer may be more than 100,000 years old. Some water may be just days old.

Where rain hits concrete or wetlands are brought under the thumb of development, the water pools, barred from the aquifer and separated from the cycle.

The aquifer is the state's greatest asset and it is no wonder that it is also the most striking. To gaze into the Floridan aquifer is to catch that glimpse of panther. To stare into the black hole of a Florida spring is to understand the wildness that left Florida as America's Last Frontier. To feel the exhale of groundwater from a Florida spring is to feel the breath of life itself.

Yet its mystery is also our undoing. Our tenuous understanding of the river coursing beneath our feet leaves a margin of error wider than the Okeechobee and more perilous and threatening than a sinkhole. That leaking pipe, that sprinkler running in the rain. That corporate interest legally pilfering millions of gallons a day, then bottling and selling it right back.

As the aquifer goes, so goes the state.

Com*pan*ioned. Com*pan*ioning. Com*pan*ions. (tr.v.). to be a companion to; accompany.

Sidney Clopton Lanier, a Confederate soldier, poet and musician, came to the Ocklawaha River in 1875. Writing a guidebook on Florida, Lanier took a steamboat up the Ocklawaha to Silver Springs.

Lanier wrote:

"Sail, sail, sail through the cypresses, through the vines, through the May day, through the floating suggestions of the unutterable that come up, that sink down, that waver and sway hither and thither; and so shall you have revelations of rest, and so shall your heart forever afterwards interpret Ocklawaha to mean repose."

At night, fires were lit on the steamboat to illuminate the river ahead. There was no dam to block the steamboat's path. There was no pool of water held back by a dam. There was no leftover debris from construction of the pool, no illegal occupation of public land, no taxpayer dollars soggily wasting away in backed-up waters.

There was no stump-field of broken trees to navigate.

There was only water pouring out of the aquifer. There was only water seeping down from the hills, carrying the memory of wind on a lake, of birds roosting in marsh.

There was only a river.

There was only a companion, lapping against the bow of the boat on a dark night. Moving freely beneath the hull. Inviting the curious, the wayward, the fascinated.

Previous: Florida officials determine maximum allowable harm to rivers, springs